Few of us will have remained unmoved by the sight of hundreds of our fellow human beings packed into unseaworthy craft and left drifting helplessly in the Mediterranean, in their struggle to escape the carnage and oppression of the Middle East and parts of West Africa. The horrors that drive these people to such desperate actions must be grim indeed. Hope and despair in equal measure aboard flimsy craft.

Few of us will have remained unmoved by the sight of hundreds of our fellow human beings packed into unseaworthy craft and left drifting helplessly in the Mediterranean, in their struggle to escape the carnage and oppression of the Middle East and parts of West Africa. The horrors that drive these people to such desperate actions must be grim indeed. Hope and despair in equal measure aboard flimsy craft.

Though acted out in hugely different circumstances, their plight brings to my mind the story of one of my wife’s ancestors, James Smith, who was shipwrecked in mid-Atlantic in 1854.

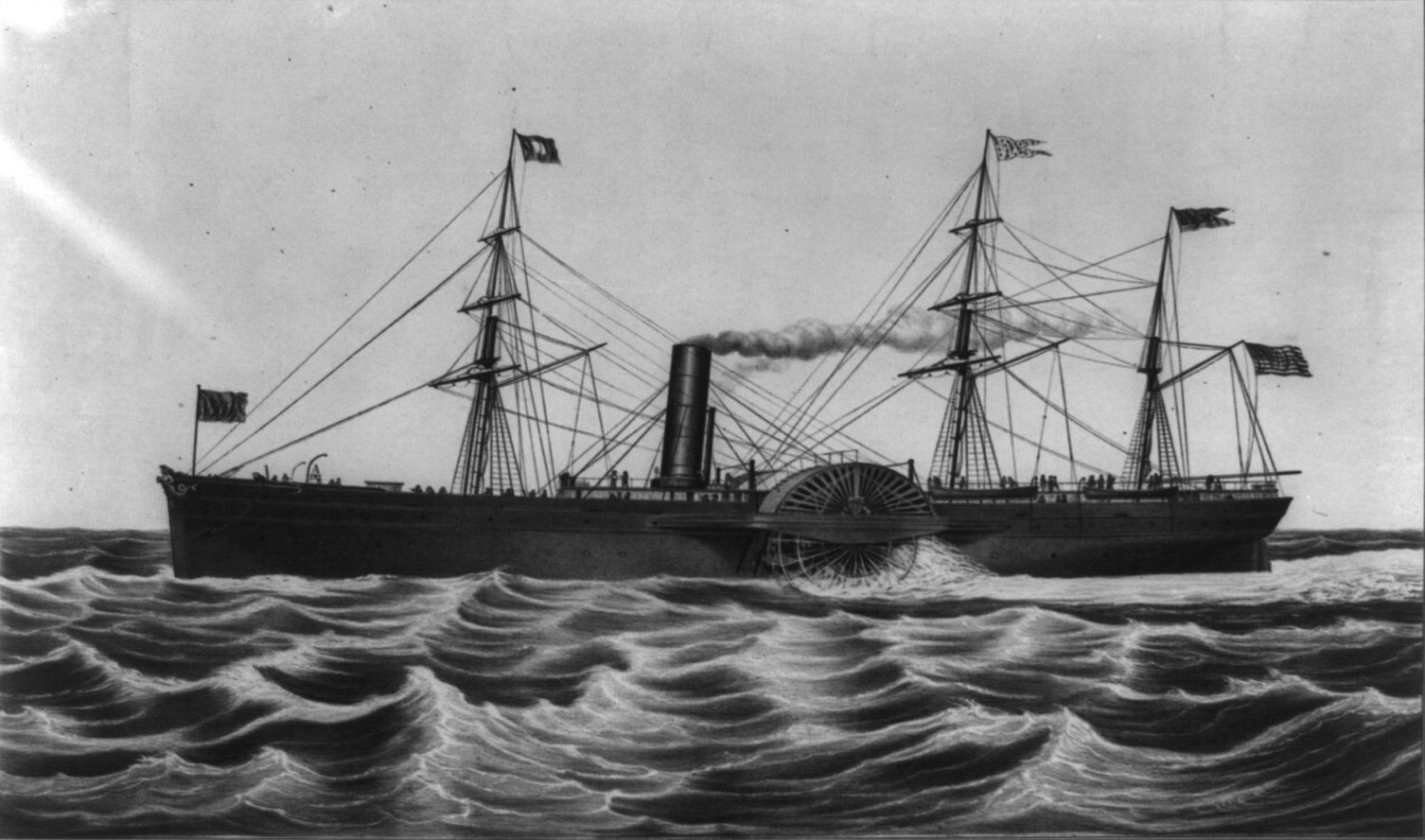

Originally from Edinburgh, James was on his ninth crossing of the Atlantic, having established a successful business in Mississippi some years earlier. Sadly his wife became ill because of the climate, and they agreed that she should return to Edinburgh with their three youngest children. His intention on this visit to America was to sell the business and return to Scotland to rejoin his wife. He travelled aboard the SS Arctic, one of the largest paddle steamers to ply the Atlantic, from Liverpool to Boston.

At sea, the voyage settled into a predictable rhythm – the swish of paddles stirring a benign ocean, conversation with fellow passengers, life in a shared cabin and the low throb of engines kept running by the unseen firemen and stokers below decks – muscle-bound men, whose duty was to keep the engines fed with coal so that the enormous paddles could propel them at a steady 12 knots across the Atlantic to Boston. Captain Luce of the Arctic had his son with him and the lad was occasionally seen with his father, touring the passenger decks. Near the end of her voyage, the north-west Atlantic fog descended and James noted that the ship did not slow down or sound an intermittent warning horn.

Late one afternoon, there was a sudden shouting from crew members, followed by a dull thud. James rushed out on deck to see what was happening. He was just in time to see a small steamer – the Vesta – disappearing into the mist. It seemed the Arctic had collided with the other vessel. There did not appear to be significant damage to the Arctic but in a brief lifting of the fog it was possible to see that the Vesta had sustained damage to her bow. Shouts could be heard through the mist.

Believing his own vessel undamaged, Captain Luce ordered first officer and senior crew to take to a boat to see what assistance the Vesta required. Other crew members lowered another boat to ascertain the extent of the damage to the Arctic. James noticed she was listing to starboard and crew appeared to be rushing around in panic. Other boats were lowered, and crew and some passengers started jumping into them. The normally unseen stokers appeared on deck and used their muscle to assure themselves of places on the lifeboats. James saw three fellow passengers lashing planks together to form a raft. Meanwhile nothing could be seen of the Arctic’s first officer and crew who had set sail for the Vesta. Distant screams of terror suggested the worst.

The engines of the Arctic had stopped – either overwhelmed by water or because the stokers had left their posts. The ship listed more and more perilously. Captain Luce could be seen with his son on top of the paddle box attempting to direct operations. There was general panic.

Taking his cue from fellow passengers, James lowered himself onto a piece of floating wreckage and paddled away from the ship. Moments later the Arctic plunged stern first into the sea, leaving floating wreckage, a few struggling bodies and two lifeboats laden with people. James remained afloat on his fragile timbers for several hours until daylight faded. There was a deep silence, a gentle swell on the sea and occasionally in the distant murk a piece of wreckage. As he floated there, seventy miles from land, he was aware that amongst some wreckage there was a large steward’s basket, the kind of zinc-lined, wicker basket used for carrying plates. With considerable effort he pulled the basket on to his raft and climbed into it.

This basket was James’ home for three days. He was aching with hunger and thirst and beginning to despair of ever seeing home again when he saw a ship emerge from the gloom – this was the Cambria, en route to Quebec. She had already picked up survivors from the Arctic, and James was one of the last. He was hauled on board, cold and stiff, and begged the crew to save the wicker basket as a reminder of his miraculous survival. The Cambria sailed on to Quebec, and James eventually travelled on to Mississippi. Amazingly, the Vesta did not sink but limped into Quebec shortly before the Cambria.

The sinking of the Arctic was one of the greatest marine tragedies of the 19th century – of the 383 passengers and crew, 21 passengers and 54 crew survived – no women or children survived, and there were many questions about decisions made by Captain Luce and the crew. As a result of a comprehensive investigation by the American Department of Transport many regulations relating to maritime transport were changed.

James Smith returned to Scotland to rejoin his wife and family, but he also left behind family in America – the “Smith connection” as they are known in Johanna’s family. To this day, they have retained “Cambria” as a family name for girls in memory of the ship that rescued their forefather.

On return to Scotland, James Smith went on to found the firm of Smith and Wellstood, at Bonnybridge near Falkirk, manufacturing cast iron range cookers. Business flourished and they launched their now famous Esse brand of stoves and cookers. Until recently, on the Esse website, there was a picture of him, looking the complete Victorian patriarch, and beneath it the story of his survival in the wicker basket. (Note to the manufacturers: Why not restore that image and story to your website?)

On return to Scotland, James Smith went on to found the firm of Smith and Wellstood, at Bonnybridge near Falkirk, manufacturing cast iron range cookers. Business flourished and they launched their now famous Esse brand of stoves and cookers. Until recently, on the Esse website, there was a picture of him, looking the complete Victorian patriarch, and beneath it the story of his survival in the wicker basket. (Note to the manufacturers: Why not restore that image and story to your website?)

While on the Cambria, James Smith wrote a closely observed account of the sinking of the Arctic which appeared in the Quebec Chronicle on 14th October 1854. Reading his account, the sheer understated spirit and humanity of the man reaches across the years. We are proud to have a copy on our bookshelf.

Like today’s refugees, James must have felt hope and despair in equal measure – but, perhaps only a fraction of the terror felt by those poor souls drifting in another sea, in our own times. I am certain that he would have been hugely moved by their predicament.

If any readers of this blog know any more about the events surrounding the sinking of the Arctic, or about James Smith’s survival I’d be delighted to hear from you.