Responding to a recent survey on stroke care from the Scottish Government, I made the point that in stroke care psychological and emotional therapy should be provided where needed alongside physical therapy. In hindsight, I now feel even more strongly about this than I did during my time as a patient. I looked back at what I had written about it in my book Man, Dog, Stroke in 2011, and I quote one of the relevant passages below. I should say that in many ways, stroke care in Scotland has moved on – though not enough. In particular, the culture around nursing care in Aberdeen is now very different from the experience I describe below. I feel I can say this with some certainty, having just stepped down after four years as a non-executive director of NHS Grampian. I am not so sure about the emotional and psychological care available to stroke patients and their carers.

Responding to a recent survey on stroke care from the Scottish Government, I made the point that in stroke care psychological and emotional therapy should be provided where needed alongside physical therapy. In hindsight, I now feel even more strongly about this than I did during my time as a patient. I looked back at what I had written about it in my book Man, Dog, Stroke in 2011, and I quote one of the relevant passages below. I should say that in many ways, stroke care in Scotland has moved on – though not enough. In particular, the culture around nursing care in Aberdeen is now very different from the experience I describe below. I feel I can say this with some certainty, having just stepped down after four years as a non-executive director of NHS Grampian. I am not so sure about the emotional and psychological care available to stroke patients and their carers.

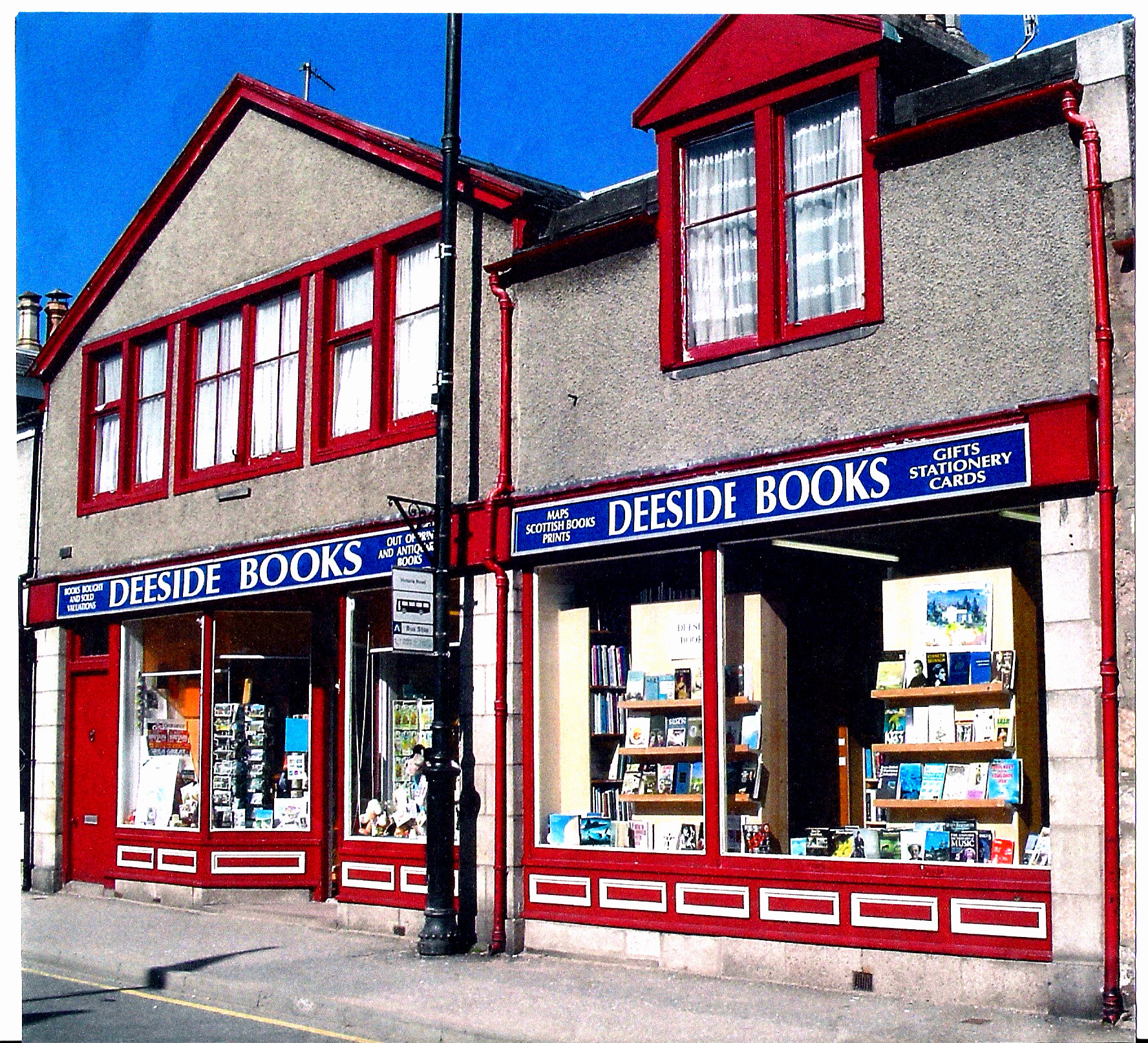

Anyway, here is the relevant extract from Man, Dog, Stroke – if you would like to read more, then simply click on the link on this blog. By purchasing a copy of the book – preferably from an independent bookshop such as Deeside Books in Ballater – you will not be making me rich, as all profits from sales go to the Stroke Association in Scotland . Towards the end of the extract, I touch on the huge matter of personal identity after brain injury, If you would like to read more about that topic, I encourage you to read Lost and Found, a very accessible book by the neurologist, Jules Montague, or my ramblings in an earlier post.

Anyway, here is the relevant extract from Man, Dog, Stroke – if you would like to read more, then simply click on the link on this blog. By purchasing a copy of the book – preferably from an independent bookshop such as Deeside Books in Ballater – you will not be making me rich, as all profits from sales go to the Stroke Association in Scotland . Towards the end of the extract, I touch on the huge matter of personal identity after brain injury, If you would like to read more about that topic, I encourage you to read Lost and Found, a very accessible book by the neurologist, Jules Montague, or my ramblings in an earlier post.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

“Akershus Hospital had been striking for its sense of calm, despite the adjacent enormous building site. Ward 11 of Aberdeen Royal Infirmary was a raucous cacophony of noise. It was Saturday evening when I was wheeled in on a trolley. Near my bed a large television set flickered garishly and trashily, the volume turned to maximum. To one side I was aware of a rank of inert elderly patients. In a room attached to the end of the ward I could hear the incessant, desperate shout of a woman calling “Nurse! Nurse! Nurse!” In another corner of the ward a gaggle of nursing staff shouted, belched, swore and gossiped at the top of their voices. They appeared to be oblivious to the noisy, desolate, hellish scene around them, seeking only to shout above it.

“Akershus Hospital had been striking for its sense of calm, despite the adjacent enormous building site. Ward 11 of Aberdeen Royal Infirmary was a raucous cacophony of noise. It was Saturday evening when I was wheeled in on a trolley. Near my bed a large television set flickered garishly and trashily, the volume turned to maximum. To one side I was aware of a rank of inert elderly patients. In a room attached to the end of the ward I could hear the incessant, desperate shout of a woman calling “Nurse! Nurse! Nurse!” In another corner of the ward a gaggle of nursing staff shouted, belched, swore and gossiped at the top of their voices. They appeared to be oblivious to the noisy, desolate, hellish scene around them, seeking only to shout above it.

I wanted to run. Failing that (and obviously I did), I wanted to be back in the soothing calm of Ward S9 Akershus. Communication might sometimes have been a problem, but at least there was a general background of peace and quiet. Above all, the staff there did not shout in the presence of patients and there was no television set in the ward. During my stay in this Aberdeen ward, it seemed to me that no-one had trained the staff to look hard at how the hospital experience might appear from a patient’s point of view. A few individuals did try to make this leap of imagination and they stood out like gold nuggets in a shale pile, but on the whole, for the patient who was feeling tired and unwell (and surely that must be the majority), Ward 11 did not seem to be the place to find inner calm.

On my first full, working day in Aberdeen Royal, I was wheeled into the physiotherapy department to be assessed briefly by a harassed physiotherapist. Later in the day I was told by a young doctor that the ward I was in was really intended for ill people, and that, since I didn’t fall into that category (I assumed he was joking) as soon as a bed became available I would be moved to the Stroke Rehabilitation Unit at Woodend Hospital, a short distance away. No-one could tell me how long I would have to wait for this, but many described the Woodend Unit as a kind of stroke survivor’s heaven (“they do wonderful things there” was a typical comment), providing first class, frequent, intensive physiotherapy and general care. I assumed this would mean resuming the daily physiotherapy I had enjoyed in Norway and looked forward eagerly to the transfer there. It was now two weeks since my stroke, and I knew from the Norwegian physiotherapists that it was important to get active as soon as possible to promote recovery. I still had a vague and somewhat naïve view of what the word “rehabilitation” meant in the context of Woodend Hospital’s “Unit”. “Woodend” had a pleasantly sylvan ring to it. In my more upbeat moments, I pictured in my mind miserable paralysed patients being wheeled in there one day on a stretcher and then on another day a few weeks later striding happily and confidently out, throwing away all sticks and walking aids, having been put through an intensive programme of physical restoration all to a background of leafy calm.

I had this view partly because I still regarded the consequences of the stroke as purely physical – in my case, an arm and a leg, and to some extent a mouth, face and voice, would have to be put right with a series of tedious but necessary exercises. After all, you get ill, you go to hospital, they hurt you for your own good, you get cured, you leave, you resume your life. Isn’t that how it works?

Not with stroke.

Stroke is both instant and insidious, and every stroke is different. In simple terms, the initial “insult” – in my case a blood clot – starves part of the brain of oxygen. If the oxygen supply is not restored within a short time, the brain cells in that locality die, and so the parts of your body controlled by those cells cease to function. The body’s rather miraculous repair process gradually allows other parts of the brain to take over the functions of the dead cells (at least that’s the theory), hence recovery, which may be over days, weeks, months, years. No medical person can honestly put a time limit on how long any individual will take to recover – or indeed how fully they will recover. Awkward for the patient. Awkward for the medical staff. Awkward for the bean counters who control the system. With our money, our beans.

Stroke is both instant and insidious, and every stroke is different. In simple terms, the initial “insult” – in my case a blood clot – starves part of the brain of oxygen. If the oxygen supply is not restored within a short time, the brain cells in that locality die, and so the parts of your body controlled by those cells cease to function. The body’s rather miraculous repair process gradually allows other parts of the brain to take over the functions of the dead cells (at least that’s the theory), hence recovery, which may be over days, weeks, months, years. No medical person can honestly put a time limit on how long any individual will take to recover – or indeed how fully they will recover. Awkward for the patient. Awkward for the medical staff. Awkward for the bean counters who control the system. With our money, our beans.

And there’s more.

The body is not like a computer where you can replace a faulty circuit with a new one. The body feels. The body is alive with present perceptions, past memories and future hopes. The body is human, and therefore unpredictable. So far as I could see, the medical “experts” in Aberdeen seemed to be treating my body more like a machine than a human being with a past, a present medical condition and – hopefully – a future. No one in Aberdeen spent time with me answering the huge pressing questions that constantly occupied my mind.

As I lay rotting in Ward 11, listening to the background symphony of elderly groans and farting, the harsh shouting of the nurses, and the braying of day-time television, I was gradually becoming more and more aware of the insidious effects of the stroke I’d suffered. During waking hours, I marshalled them in my mind, patrolled them in front of me one by one.

Concentration – gone. I could read words, but couldn’t concentrate long enough to read more than a couple of sentences. In any case, holding a book was difficult; holding a newspaper, impossible. Worst of all, I couldn’t concentrate on more than one thing at a time. No change there, Jo would say. But now it was serious. Friends had begun to visit me and I found that I couldn’t focus properly on what they were saying if there was another visitor talking at the next bed, or if a nurse was speaking at the other end of the ward, or if the television was switched on (it always was).

Speech – improving, but still hard work to form the words and string them together.

Emotions – in turmoil, and out of control. I could weep for Britain. Equally, if someone made a mildly funny remark, I could not contain my bursts of laughter. Surely it could only be a matter of time before I laughed at something tragic and lost a friend forever.

Exhaustion – constant and bone-sapping. The daily routine of showering and toileting supported by wheelchair and nurse left me weak and ready to sleep. I spent the whole day in bed. I slept for hours every day. I wakened every morning as if from deep unconsciousness.

Underlying all of these side-effects, a deeper nagging question – was I really the same Eric, as I had so confidently claimed to be when Jo first came to see me in Norway. I know that other stroke survivors have felt the same – are the pre-stroke person and the post-stroke person one and the same personality? How could I know for sure?

And the biggest questions of all – was life over as I’d known it up till now? Would I recover? Would I recover completely, partially or not at all? How could I help my recovery? None of the medical staff I spoke to in Ward 11 seemed willing or able to tackle these huge questions with me.

I hoped things would be better at Woodend.”