We are told that 2014 is to be a big year for Scotland – Ryder Cup Golf, Commonwealth Games and, of course, that referendum – so, this blog’s New Year’s resolution is to spend some time during the year looking beyond Deeside, dogs and stroke. Oh, yes. There’s a big world out there just full of interest for post-stroke man of a certain age and his adolescent whippet.

We are told that 2014 is to be a big year for Scotland – Ryder Cup Golf, Commonwealth Games and, of course, that referendum – so, this blog’s New Year’s resolution is to spend some time during the year looking beyond Deeside, dogs and stroke. Oh, yes. There’s a big world out there just full of interest for post-stroke man of a certain age and his adolescent whippet.

Being as it’s midwinter, let’s go to the tropics.

Every time an election looms, I lie back and think of Cameroon. And I think back to the early 70s, to a national referendum which was held when I was working as a young volunteer teacher in a small Catholic teacher-training college in the West African country. I was the sole European amongst a teaching staff of Cameroonians. Our students came from across the country.

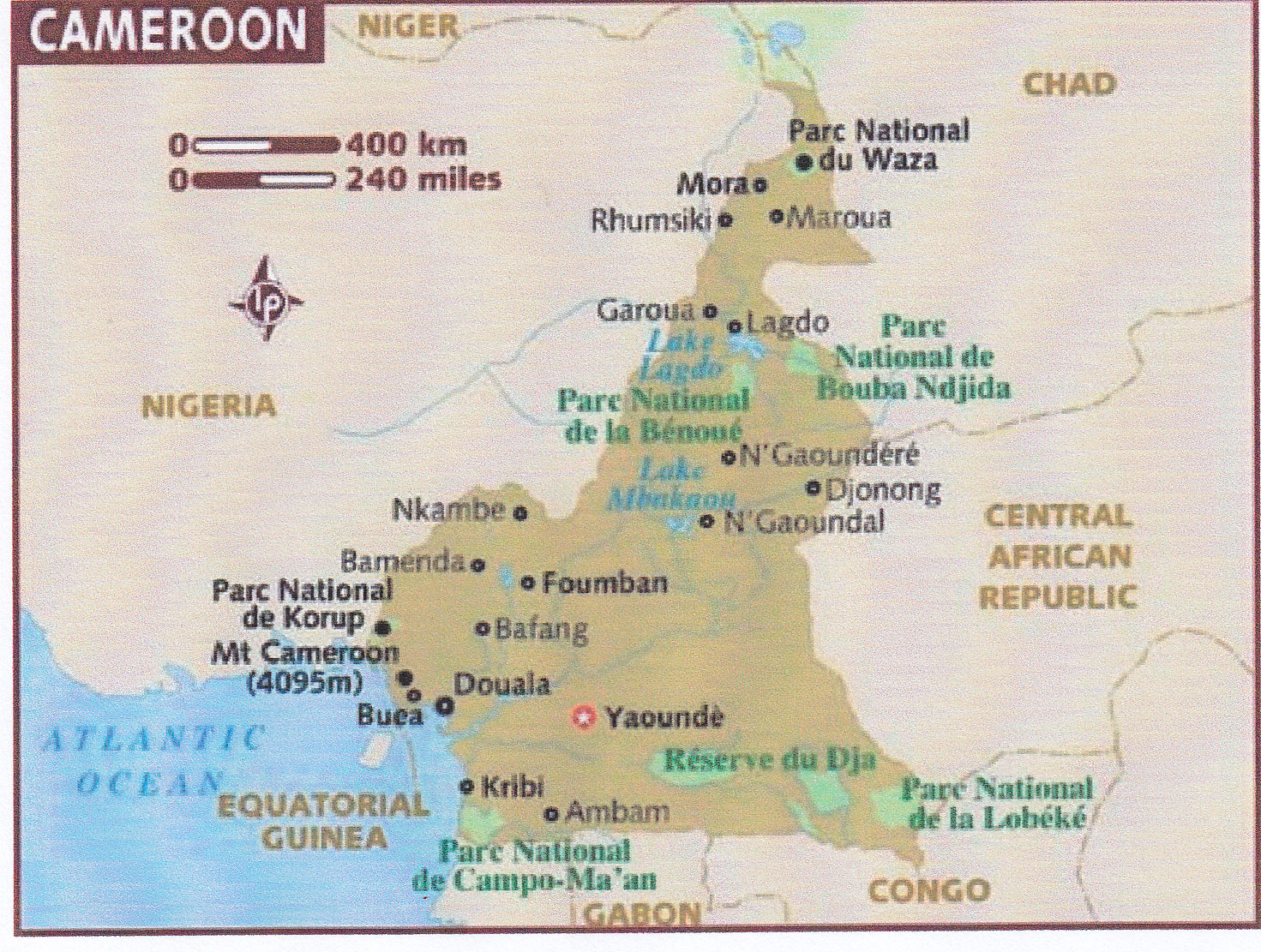

At that time, Cameroon was a federal state. It was fairly recently independent and was an amalgam of the former French Cameroons (East Cameroon) and the much smaller, former British colony, West Cameroon. There was a great deal of pride in being Cameroonian andWest Cameroonians had, in an earlier referendum, voted to join with their Francophone neighbours, rather than being subsumed into a distant part of the giant (and recently violent) state of Nigeria.

There was a national government in Yaounde, the capital, situated in East Cameroon and there were smaller federal governments, including one in Buea, the administrative capital of West Cameroon. Both French and English were (and are) official languages, although French was predominant, and the official languages were important for communication across the country as there were dozens of local languages, not one of which predominated. For example, Bakweri, the language spoken in the village adjacent to our college, was useless beyond a 20-mile radius. English-speaking West Cameroonians, being a minority in the country as a whole, were wary of the more numerous and vocal French-speaking majority. Educated West Cameroonians also had a healthy strain of humour and satire regarding politics in general and local politicians in particular. This was regularly articulated in heated discussions with trusted friends and also by a satirical columnist in the local English-language paper, the Cameroon Times. There was a real fear that this culture of cutting politicians down to size might be lost in a larger, largely francophone nation.

In 1972, President Ahidjo declared that there would be a national referendum to decide whether Cameroon should become a united republic with one central government in Yaounde, with the federal governments abolished. It was a kind of devolution referendum in reverse, I suppose. As a foreigner, of course, I had no vote. My African colleagues in St Paul’s College, always keen on lively debate, were almost universally cynical about the motives for the referendum, seeing it as an exercise in centralising power in the east, with a facade of democracy draped over it. However, it was one thing bravely speaking up amongst one another in the precincts of our relatively remote college – it would be quite another for a Cameroonian voter to declare publicly that he or she was going to vote against the government line – which was to support a resounding ‘Yes’, in favour of a united republic. As leader of the only legal political party, President Ahidjo inspired public reverence from all Cameroonians, regardless of their private thoughts about his policies and style of government.

But enough of politics and history – give yourself a laugh by clicking on the photo below to reveal the full horror of my hairstyle and the width of our flares.

Anyway, the evening before the poll I had a couple of beers with my colleague and friend, Dominic – not his real name, because I’m sure even now he’d prefer to be anonymous. Dominic was enraged by the referendum – not so much because he disagreed with the government’s plans, but because they were effectively telling him how to vote. ‘I’m going to try to vote “No”,’ he said. ‘Come with me tomorrow and see how much freedom we have in Cameroon.’

Next morning, dressed as smartly as we could, and perspiring in the humid air, we set off for the polling booth in the village. Outside the voting hut were two armed gendarmes, sporting red berets and dark glasses. This was very unusual – we never saw a local policeman in our village, let alone senior members of the gendarmerie. The local villagers were better known for their palm wine than for thoughts of insurrection. The gendarmes had the relaxed arrogance and innate self-belief of many uniformed East Cameroon Francophone officials. ‘Cartes d’identité!’ one of them said to us, intoning the ‘d’identité’ in strongly accented Cameroonian French – ‘deedangteetay’. We obediently produced our identity cards and I was ordered to stay outside while one of the gendarmes escorted Dominic into the hut.Dominic later told me that the hut contained a number of pictures of President Ahidjo and two tables, one with the word ‘oui’ on it, and the English word ‘yes’ written in very small writing beneath, together with a small pile of ballot papers. The other had a ballot box on it. The village chief was standing beside the tables. Dominic knew this man well and asked him how he could vote ‘non’. He had barely articulated his question when the gendarme pinned him to the wall and asked him what he thought he was doing. In the interests of self-preservation, Dominic meekly placed his cross on the ‘oui’ ballot paper and left the hut.Next day, we listened to the results on the radio – ‘overwhelming majority in favour,’ ‘98% support for the President in Douala,’ ‘Ahidjo thanks the people’. The referendum had achieved its purpose – Cameroon would now become a united republic.

It may be unfair to compare the efforts of a newly independent African state with our own supposedly mature democracy. However, I’ll be voting on 18 September 2014, because I am lucky to live in a democracy. No doubt reams of text and hours of telly will be devoted to the referendum – and rightly so. My vote may not be for the side that ultimately wins. But at least no one can tell me to vote oui and stop me from voting non – yet – and that’s something we have that’s beyond value, something gained through blood sweat and tears, and something worth remembering as we enter 2014.

Happy new year when it comes.

A version of this post appeared in the Scottish Review in June 2010.